As an editor in business publishing, I spend a lot of my time reading articles on various subjects—private equity, maybe life insurance, or the latest on automation in manufacturing operations. One of the issues I tend to run into is not being able to find the story. All the information is there. The authors back up their points with real numbers—but I’m still trying to add things up myself. With each paragraph I finish, I seem to know less about the subject. Five minutes later, if you ask me what I just read, I wouldn’t be able to tell you.

Of course, it’s my job to do just that: comprehending disparate information and synthesizing it into something cogent. A big part of that process is figuring out the story, which—to be fair—is easier said than done. As someone who studied creative writing, who worked in the commercial publishing industry selling memoirs and high-profile nonfiction projects, and who now teaches college-level courses on composition and rhetoric, I still think it’s hard. Finding the best story and telling it as clearly as possible is always difficult, even for the pros. But if you want people to see the world the way you see it—if you want to change minds—you have to do just that.

One of the things that inspires me—what got me into storytelling in the first place—is art history. I love to read about ancient artforms and the techniques of the masters, and I love to think about what we can learn from them. With that in mind, here are a few lessons I’ve learned from studying art history and what it says about telling a compelling story that people will remember.

Connecting with your audience

Friedrich Nietzsche believed that Greek tragedies—stories in which human suffering leads to catharsis for the audience—were able to transcend the meaninglessness of our world. In other words, experiencing the joy or suffering of others affirms our own existence. The Greeks had another term for this, “pathos,” which means appealing to the emotions of an audience. Ultimately, a story must make a connection—there needs to be some sort of appeal—and making that appeal requires knowing your audience. Are you writing for industry insiders with specialized knowledge? Or are you writing for people who need to be brought up to speed on a new technology? Are you writing about something to help businesses save money? Or to better protect the environment? Determining your audience affects not only what story you choose to tell, but how you tell it.

Discovering and sculpting your story

Sometimes it’s helpful for me to think about storytelling as if it were sculpture. Michelangelo famously said that every block of stone has a statue inside it and that it’s the job of the sculptor to discover it. Finding the story really isn’t all that different. Think of it as relief sculpture: there are big blocks of text or information that must be conveyed, and your job is to lift the story out of the text. Other times, you can think of the process as intaglio, which is when you engrave—or cut into—an object that’s already formed. In these instances, it’s your job to dig deeper or refine what’s already there. More often than not, the material you’re working with determines how you sculpt the story. If you’re writing about something that has real-world implications, such as life insurance, you’ll want to tell a story that people can relate to. A new and improved customer service journey is one thing, but if the result of that journey is better peace of mind because customers are living longer, healthier lives, you’ll want to highlight that.

Ensuring that your story has a beginning, middle, and end

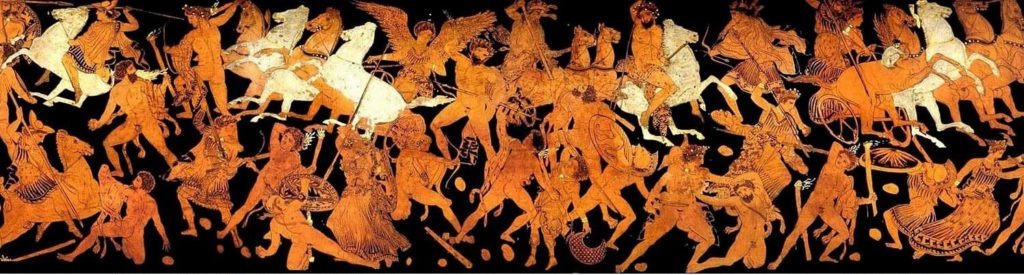

A big part of figuring out the arc of your story—its beginning, middle, and end—is thinking about how to sustain the interest of your audience. You can’t just bookend your article with interesting scenes or examples; you need to weave those narrative elements throughout. In this sense, storytelling is similar to the battle scenes or mythological tales that wrap around ancient painted urns or vases—it evolves as you follow it along. Your audience needs that sense of continuation, whereas looking at a painted urn from a single angle offers only a glimpse of something larger. Yes, an article should begin with a hook, something that captures the reader’s attention. But as the article continues, that hook should uncurl and form a through-line. If the middle of your article focuses on the complications an industry faces, you’ll want to return to that and describe the challenges in more detail.

One final thought: it’s always helpful to tether your examples to the real world, or to find something that resonates with your audience. As Keats says in “Ode on a Grecian Urn”:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,”—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

There you have it—a concluding sentiment that’s worded so well they teach it in high schools. Still, the point stands. Sometimes what matters most is simply cutting through the noise and getting to the truth. The next time you’re searching for the story, try telling it out loud in the simplest language possible. There’s a reason the oral tradition has taken us this far. Chances are, your instincts will get it just right, and you’ll be able to translate it to the page that much better.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.